The Carillon: Living Heritage is Music to Everyone’s Ears

From livening up a traditional student sing-along to a surprising rendition of a modern pop ditty; ever since UNESCO recognised the Belgian carillon culture as part of our intangible cultural heritage in 2014, fans of the musical instrument have gone all out to get rid of its somewhat stuffy reputation. The carillon, which is inextricably linked to the Low Countries, is looking to reconnect with a wider audience. Contemporary carillonneurs are committed to promoting their belfry melodies as living heritage to anyone who’s willing to listen.

The fact that we are still able to enjoy the bells of the carillon is nothing short of a miracle. Since its inception in the 16th-century Southern Netherlands, up until the 1800s, the carillon served its purpose as a local musical mass medium. Soon afterwards its natural role in society started to slowly diminish to the benefit of the pianola, the barrel organ, the gramophone, the radio, CDs and streaming music consecutively. Nevertheless, the carillon is well on its way to surviving some of its successors.

Carillonneur Jef Denyn founded the Royal Carillon School

Carillonneur Jef Denyn founded the Royal Carillon SchoolJef Denyn (1862-1941), a Malinois carillonneur, played a crucial part in the carillon’s survival. Around 1890 he improved the carillon’s mechanical equipment, and between 1900 and 1930 he managed to turn the Monday night concerts in Mechelen into the city’s go-to events. In 1922, – with a little help from a few fellow townsmen and an injection of American dollars – he started a carillon school in Mechelen. The prestigious Royal Carillon School continues to be an internationally renowned institution. In short: if it hadn’t been for Denyn, the art of carillon would not be where it is today.

Fully-fledged concert instrument

Paradoxically, Denyn planted the seed for what would eventually cause a rift between the carillon and its audience. Denyn was devoted to the carillon’s emancipation from a humble folk instrument to a fully-fledged concert instrument. To accomplish this, he developed a virtuosic and expressive style characterised by tremolos, and as such gave rise to a ‘classical’ repertoire of original carillon music. Although Dedyn’s music sounded phenomenal and magical, lesser carillon gods’ fists would later be responsible for a rather obtrusive and obnoxious sound.

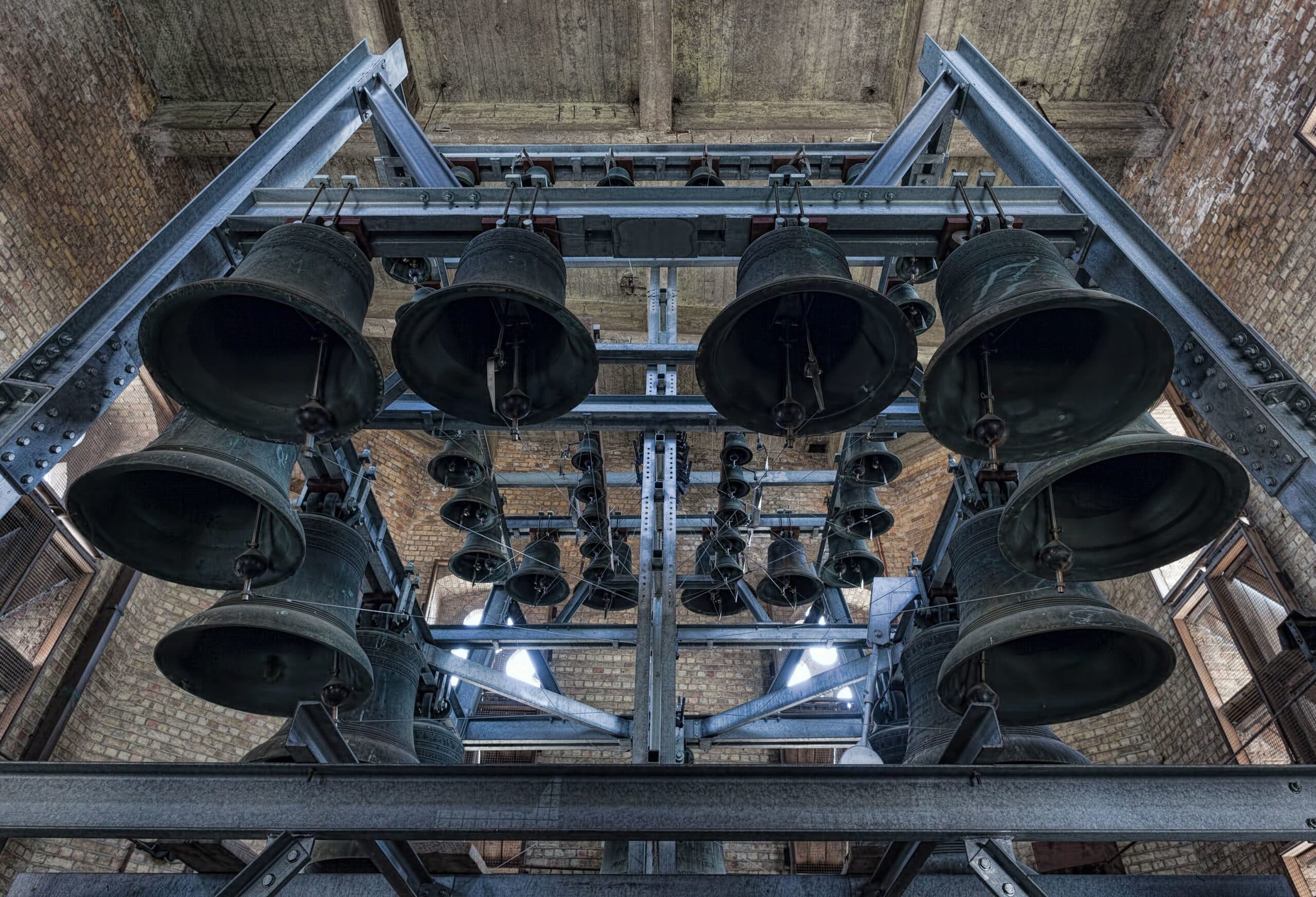

20th-century carillon in the belfry of Ypres

20th-century carillon in the belfry of Ypres© Andreas Dill

A similar evolution took place in the Netherlands. The enthusiasm that accompanied the process of (cultural) reconstruction after World War II, caused the number of carillons to double in the Netherlands within a brief period of time. Carillonneurs would present themselves as artists playing brand-new well-thought out carillon music, excellent themed carillon concerts featuring musical scores composed by the likes of Henk Badings and Kors Monster, complete renditions of Bach’s suites et cetera. However, the general public was unable to identify with this type of cultural education, and carillonneurs would only be embraced by a select group of fans.

Mobile carillon

Rien Donkersloot plays the mobile carillon "Bronze Piano", Mechelen, 2014

Rien Donkersloot plays the mobile carillon "Bronze Piano", Mechelen, 2014© Thomas Koeck

Around the turn of the century carillonneurs were able to reconnect with a wider audience, owing – among other things – to the invention of the mobile carillon. Mobile carillons have been built since the fifties, but it was not until recently that they have been used in a musically sound way. Boudewijn Zwart, who used to be Dordrecht and Amsterdam’s city carillonneur, was one of the trailblazers. In 2003, he commissioned his own mobile carillon to be cast. Under the name Bell Moods he would perform concerts and organise storytelling performances aimed at the whole family.

His Maastricht colleague Frank Steijns has owned a mobile carillon ever since 2006, with which he performed many concerts accompanying André Rieu’s Johann Strauss Orchestra. Steijns also plays the violin in Rieu’s Orchestra. As Steijns performs around the world with Rieu and his fellow musicians, he is probably one of the most listened to carillonneurs in history. Their Flemish colleague Koen Van Assche and Anna Maria Reverté, Barcelona’s carillonneur, had a mobile carillon built in 2014, which is shaped like a grand piano. This Bronze Piano is intended for concerts, and is usually part of a chamber music performance.

Carillon Plus

Carillon sing-along in Leuven, 2017

Carillon sing-along in Leuven, 2017© Teun Stuart

Nowadays, carillons that are housed in bell towers offer a wide range of creative possibilities as well. ’Carillon Plus’ is a collective term for performances during which the carillon breaks away from traditional rules and is accompanied by various instruments or other forms of artistic expression. In 2000, this culminated in a spectacular, highly attended student sing-along accompanied by the carillon at the Ladeuzeplein, a square in the centre of Leuven.

Following on from that initial event, most Flemish university cities started to organise their own versions. In 2010, the city of Bruges organised a musical dictation contest led by the carillon in the town’s Belfry. Moreover, in that same year visitors were invited to play the famous instrument themselves during the so-called ‘cacophony concert’. In 2017, the Antwerp carillon bells could be heard ringing alongside girl band K3 and DJs Dimitri Vegas and Like Mike. At the moment, nearly every carillon city organises these ‘Carillon Plus’ concerts quite regularly. ‘Carillon Plus’ is an excellent way to draw the general public’s attention to the carillon. Nevertheless, ‘ordinary’ carillon music remains at the heart of carillon culture. The sound of those bells is a quintessential part of the general Low Countries’ mood.

"Carillon Jam" in Hasselt in 2014: dj Courtasock and carillonneur Jan Verheyen

"Carillon Jam" in Hasselt in 2014: dj Courtasock and carillonneur Jan Verheyen© Stefan Nieuwinckel

Carillon as communicator

Now more than ever carillonneurs are realising they should adapt their repertoire to the invasive sounds of their instruments and to their ever more diverse audiences. More often than before they play music befitting special occasions with some kind of societal relevance, whether it is to celebrate the local sports team’s championship victory, or to console the devastated community after a terrorist attack. They perform the communicative task the tolling church bells used to take on. When musicians pass away, the bells of the carillon mourn with us by spreading the deceased’s greatest hits all over town. 2016 was a particularly busy year when it came to saying goodbye, and a great many carillonneurs all over the Low Countries played their instruments to honour artists such as David Bowie, Eddy Wally, Prince, Toots Thielemans, and Leonard Cohen.

These renditions are often shared on social media platforms, which is a successful way of supporting the carillon, a more traditional musical medium. The audience themselves also have a bigger say in the kind of music which can be played on the carillons with, for instance, Jukebells. The general public can use this online platform to vote for the songs they want to hear played on their town’s carillon.

Social connection

The carillon’s newfound love for popular music does not mean classical music will be shunned. In fact, the carillon repertoire is dictated by each town’s unique individuality. Housed in the Dom Tower of Utrecht, the well-known 17th-century carillon treats audiences to classical music from the Baroque period during the annual Early Music Festival. At the same time, carillonneurs are aligning their repertoire with today’s super-diverse society. One of the initiatives worth mentioning here is the Big Rotterdam Songbook (Groot Rotterdams Songbook). In 2018 and 2019, all three Rotterdam carillons played children’s songs belonging to the one hundred and seventy nationalities living together in the city. This project’s success emphasises how the carillon can be a powerful step on the road to increased social connection.

It’s wonderful to see how an increasing number of towers are open to the public, allowing visitors to learn about carillon heritage. The Belfry of Bruges, for instance, has about one hundred thousand visitors a year. The two enormous carillons in Mechelen’s St. Rumbold’s Tower are well on their way to becoming a hit with tourists as well, as about forty thousand people climb to the top of the tower every year. Down on street-level, one can browse through comprehensive collections spanning decades of carillon heritage at the National Carillon Museum Klok & Peel in Asten, and at the Museum Vleeshuis in Antwerp.

Contemporary carillons

The Low Countries are the only area in the world where nearly every city and most large towns are home to a carillon. In the city centres of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Mechelen and Leuven three or more carillons ring their bells from the various bell towers. You might get the impression that the carillon market in the Low Countries is completely saturated, and there is no more room for additional carillons. The sound of a carillon, however, only has a limited range. Therefore, there is still a lot of unchartered territory for carillon enthusiasts around these parts. Recent installations of carillons in Vleuten, Neerpelt and Puurs prove that also smaller residential areas become even more charming and gain a sense of identity thanks to carillon music. This could give the new momentum to the manufacture of carillons, bells and chimes. Worldwide, the Low Countries have the strongest tradition of bell foundries and carillon builders, Royal Eijsbouts bell foundry located in Asten, North Brabant being the clear market leader.

From the keyboard room in the Dom Tower of Utrecht, the carillonneur has direct visual contact with the historic city centre

From the keyboard room in the Dom Tower of Utrecht, the carillonneur has direct visual contact with the historic city centre© Luc Rombouts

In French Flanders, historically one of the core regions of carillon tradition, things aren’t moving quite as fast. The carillon is a phenomenon that is deeply rooted in local customs, which you can, for instance, notice from the link in Douai and similar towns with the local annual giant processions. Several carillons will play the Reuzegom to accompany the swaying giants. In 2008, French Flanders’ carillon culture received an unexpected boost thanks to Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis, a film directed by Dany Boon. The director himself also played the part of Antoine Bailleul, a postman in Bergues and carillonneur at the local belfry. The film – which about twenty million people watched in cinemas, and bumped the tiny town of Bergues to tourist hotspot – introduced the world to traditional Low Countries’ carillon music.

It’s not every year carillon culture is showered with a similar amount of attention. Still, the continuous efforts made by carillonneurs and associated carillon workers have been paying off, and continue to do so. Low Countries’ carillon communities are increasingly promoting the music emanating from the bell towers as living heritage. Moreover, they work hard on implementing UNESCO’s 2014 requirements in order to make carillon culture an art form fit for the 21st century.